Bad news: No one is immune to propaganda. That’s because the best propaganda doesn’t even try to change your mind. Instead, it takes what you already know or believe and builds connections to its own agenda.

How does it do this? By finding a shortcut around your rational decision-making skills and all the years of life experience that usually help you sniff out suspicious claims.

Making good decisions requires asking questions. Is this the best product to buy? What policies does this politician support? Is this medical treatment safe?

Propaganda doesn’t want you to ask these questions or find the answers. It uses manipulative techniques — simplification, exaggeration, exploitation and division — because it wants you to leap to conclusions based on feelings, not facts.

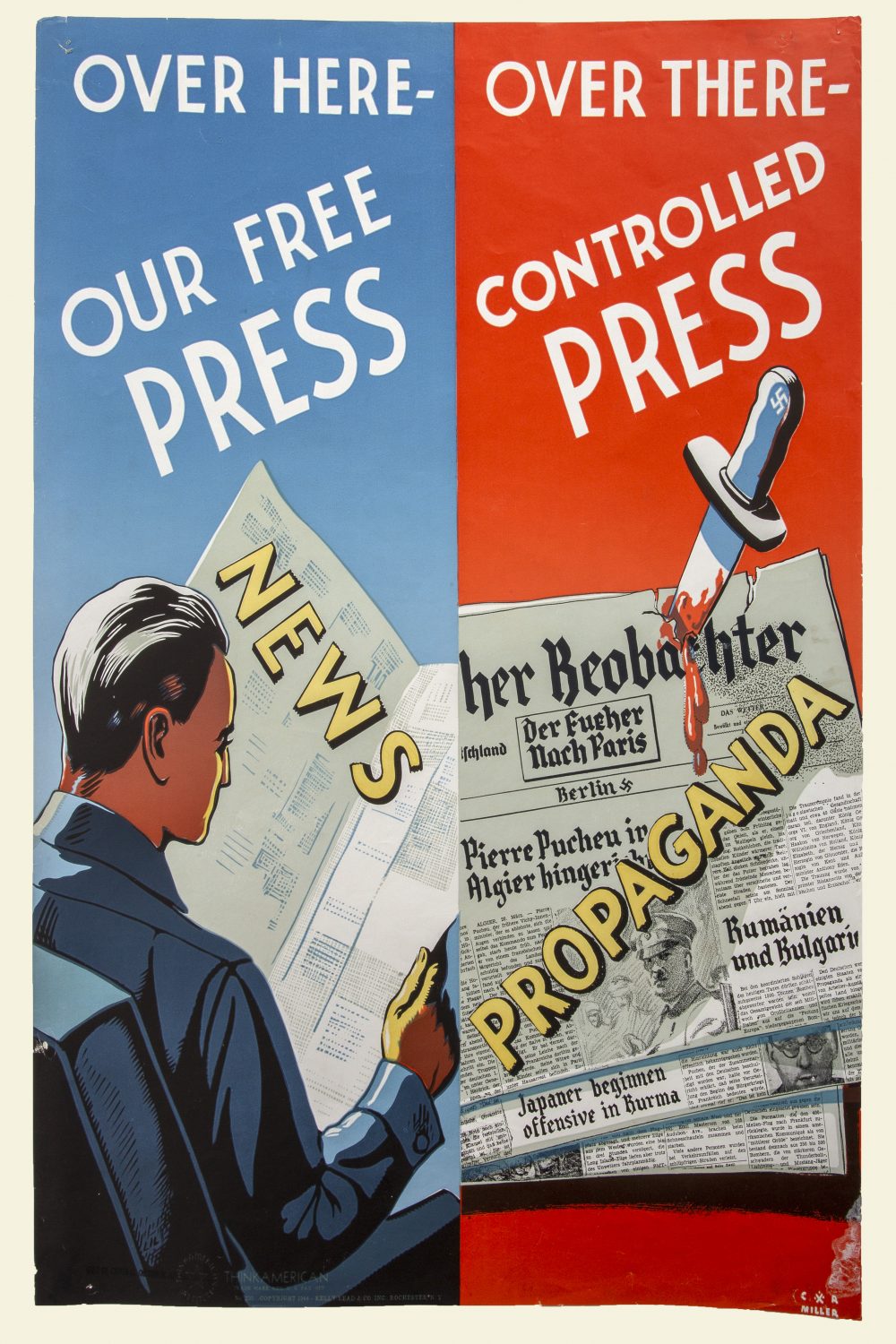

In the United States, the First Amendment protects online information and expression with very few limitations. On the one hand, that means that many forms of propaganda can circulate freely.

On the other hand, that means that there is a wealth of information available to help us weigh our important decisions. Whether we need to decide who to vote for or where to spend our next vacation, the First Amendment ensures we have plenty of resources to draw on. By tapping into this information and asking the questions propaganda wants us to circumvent, we can make the pros of free speech outweigh the cons.

We all pay a price for the irrational decisions and actions that propaganda encourages. Whether we’re the ones making bad choices or the ones stuck on the receiving end, there are many ways that propaganda can negatively impact our individual lives and society.

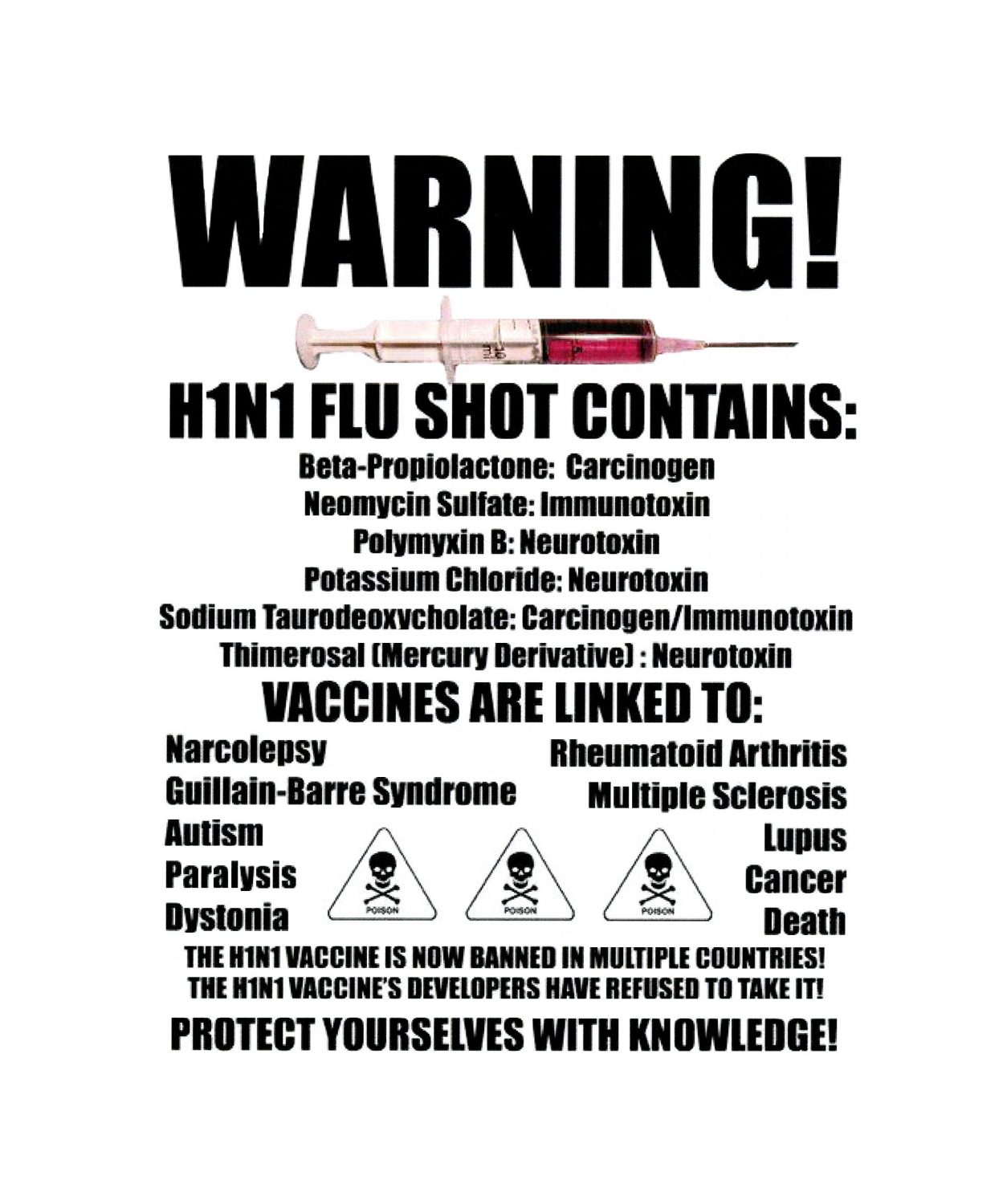

Falling prey to propaganda can lead to unnecessary spending on everything from fake health cures to sham charities. For example, websites that spread disinformation about research-backed scientific treatments often throw in a pitch to buy their own “natural” alternatives. And once they’ve convinced you that traditional medicine is the real waste of money, purchasing untested and unregulated supplements seems a lot less crazy.

Unscrupulous fundraisers also borrow from the propaganda maker’s toolbox to squeeze more money from supporters of their cause. There’s a thin line between tugging on your heartstrings and yanking them to force you into a rash decision without doing any research.

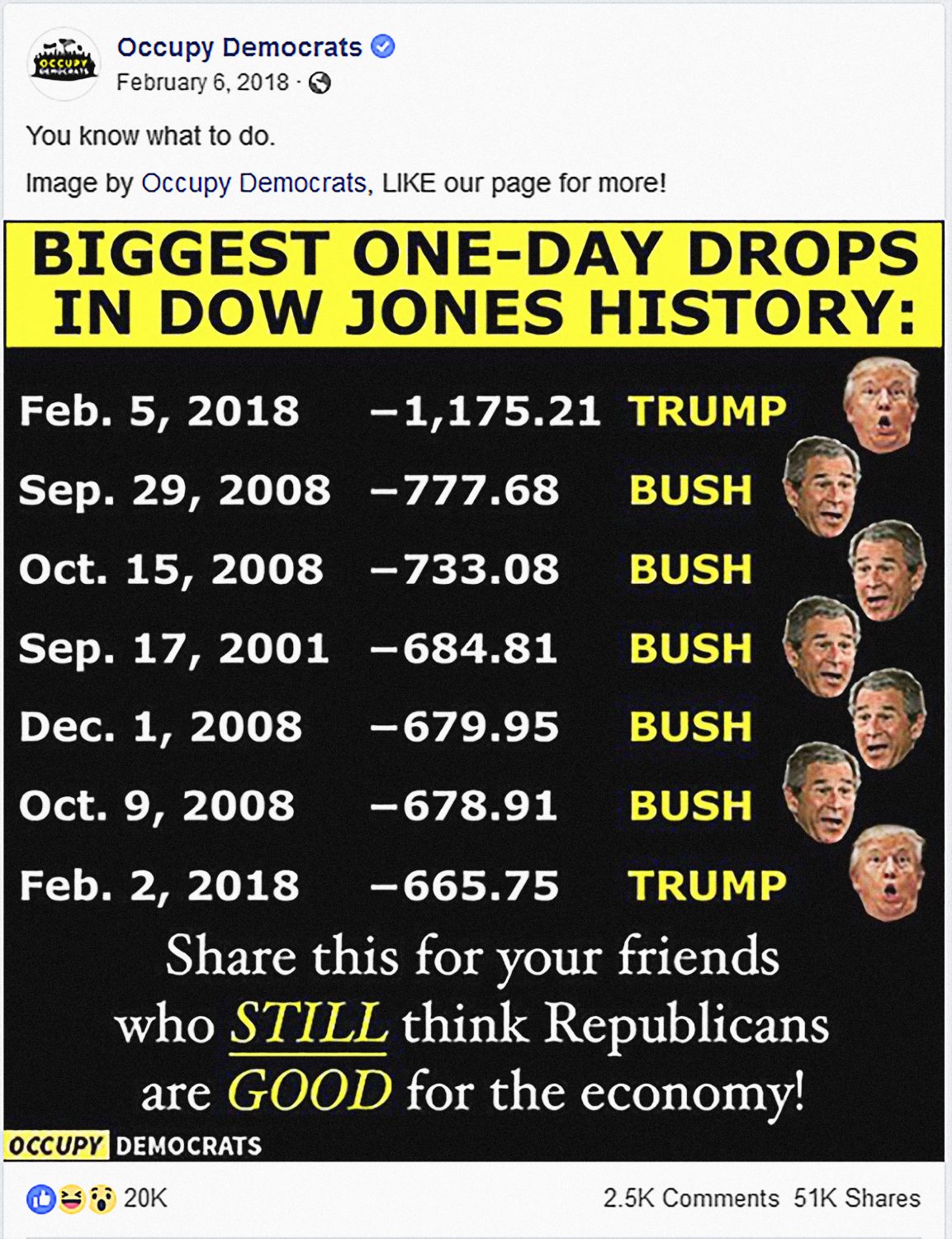

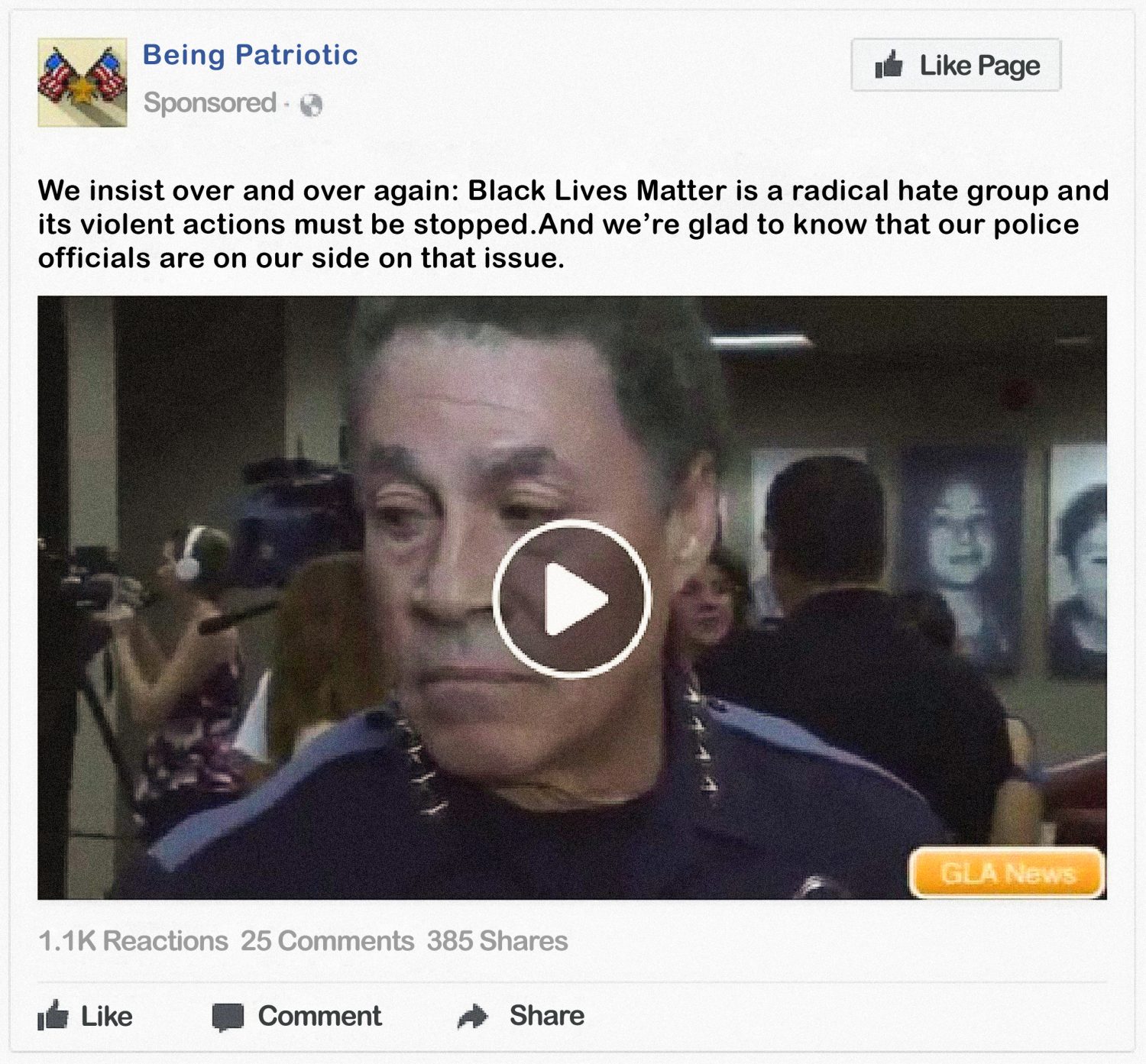

Propaganda amplifies the ideas and opinions found at the far ends of the political spectrum, and its key techniques — simplification, exaggeration, exploitation and division — don’t lend themselves to compromise or moderation. When you’re exposed to ongoing propaganda, some genuinely out-there ideas may begin to seem more normal, and opposing viewpoints may begin to seem more unacceptable.

That’s bad because solving problems almost always requires some degree of compromise. When propaganda pushes opposing groups further apart, it makes solutions that would benefit everyone more difficult to attain.

When propaganda spreads disinformation about public health issues like vaccinations or disease outbreaks, we all face increased risk. These messages exploit people’s worst fears — disease! death! — in order to bring visibility to a cause or, sometimes, just to sow chaos and destabilize the status quo.

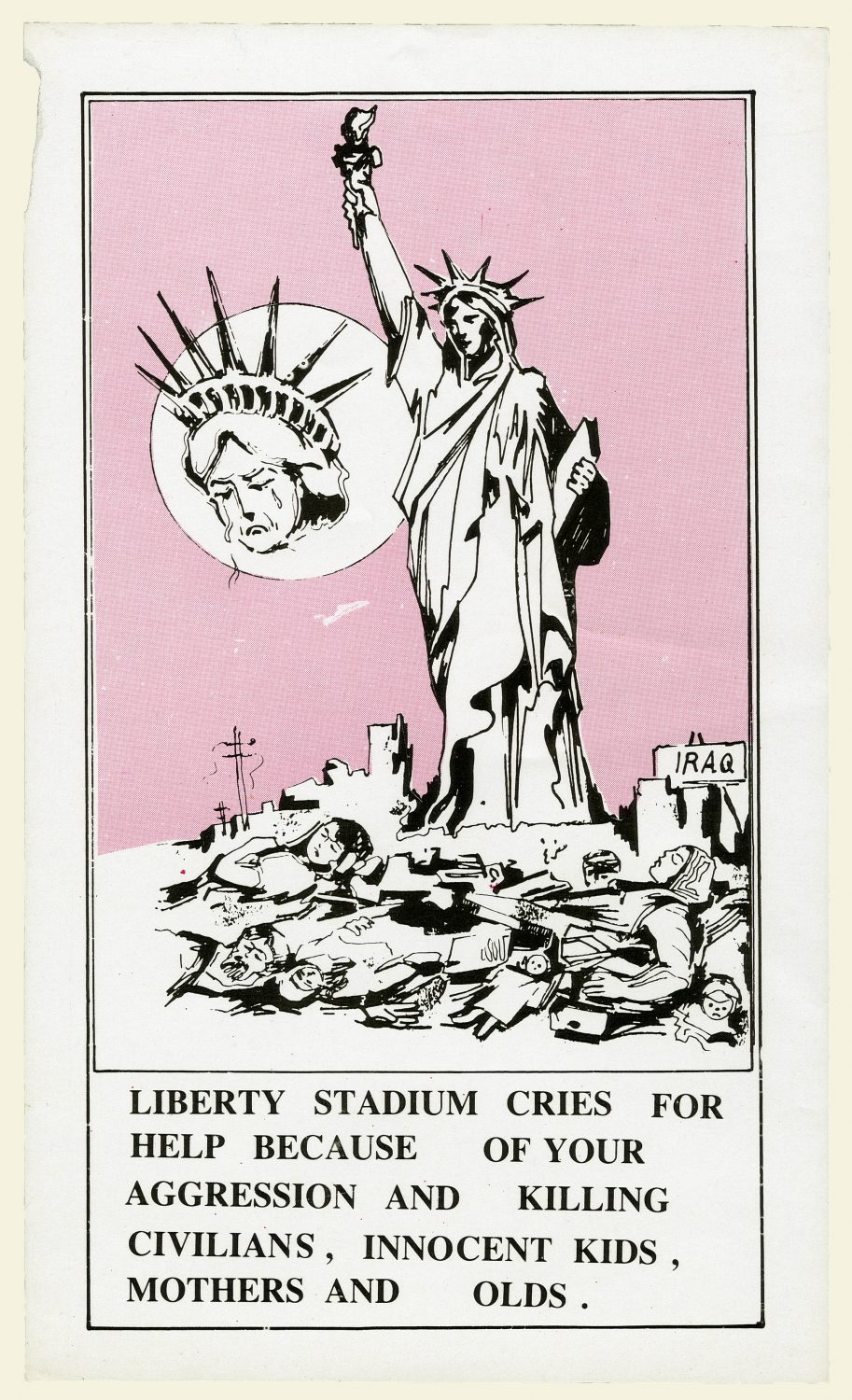

Propaganda can also endanger the public by stoking violence toward particular groups or individuals. For example, in Myanmar, military personnel used fake profiles to spread a barrage of Facebook posts attacking the Rohingya Muslim population. The posts raised fears about Islam and spread rumors of rapes by Rohingya men. These false messages fueled vicious attacks and triggered a humanitarian crisis.

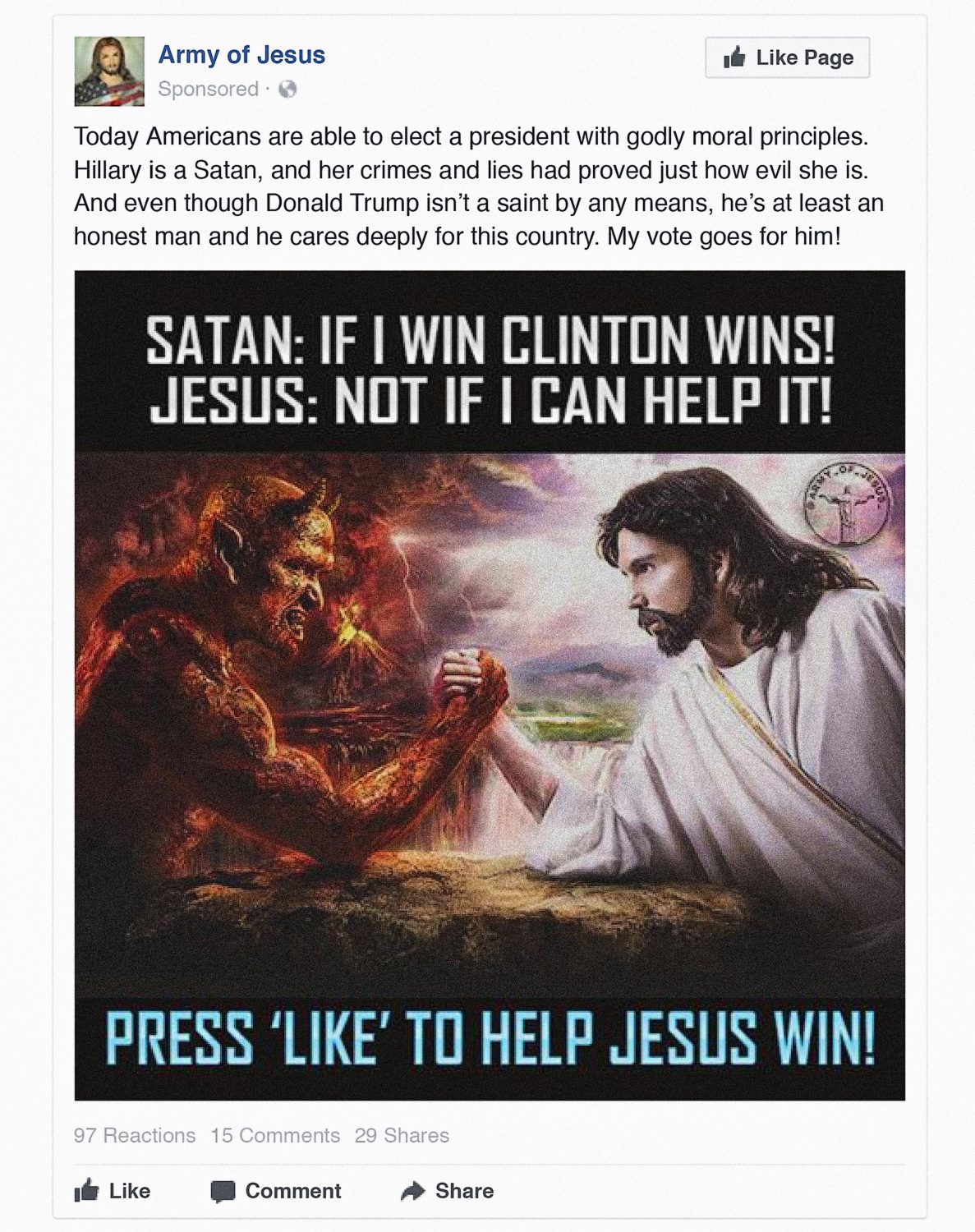

Democracies rely on the public’s ability to make reasonably informed decisions about what we want in a leader. Propaganda has long played a role in attempting to influence those decisions in the form of campaign ads produced by political players. Most voters know that a message from Candidate Smith’s campaign is likely to have a pro-Smith spin.

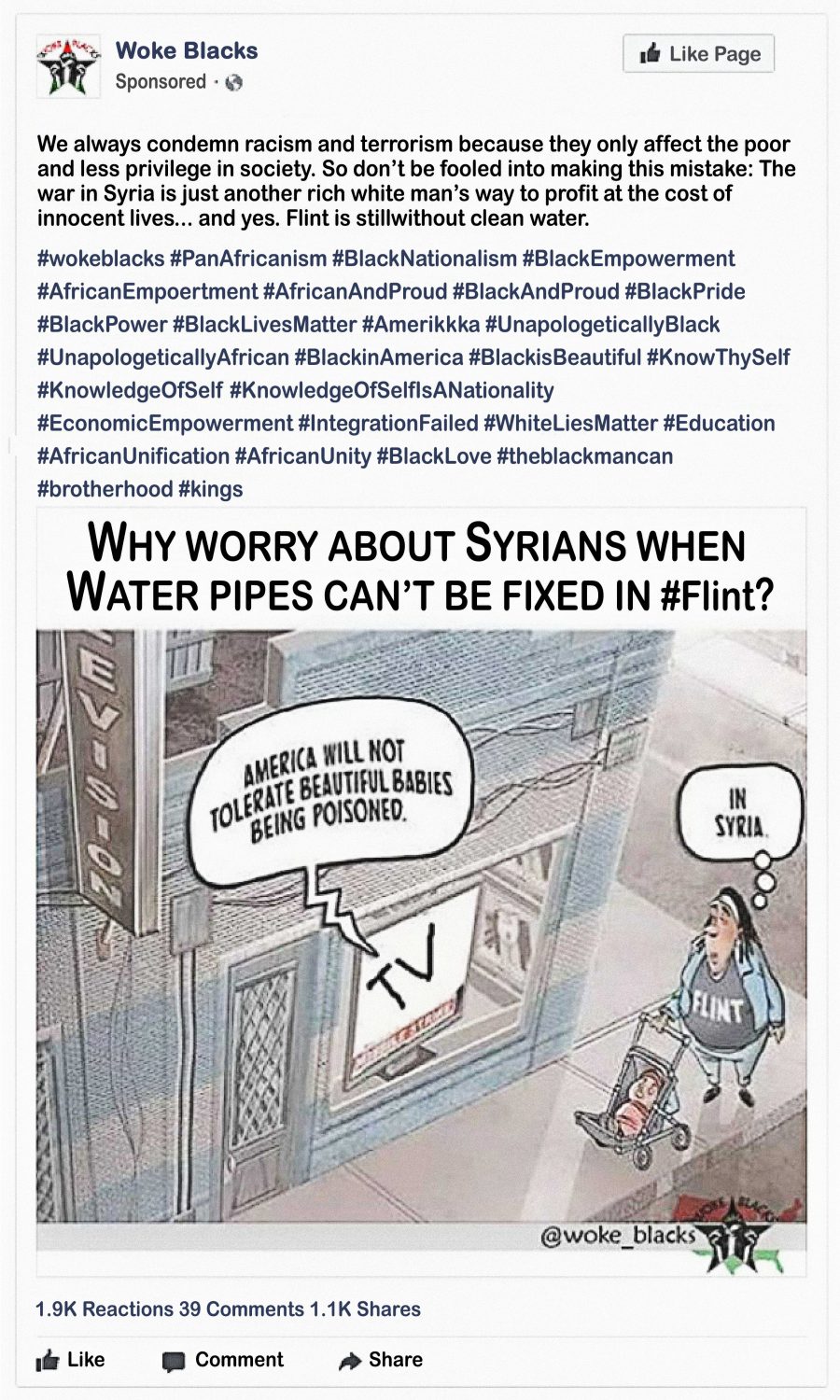

But what happens when the messages that can shape the outcome of an election aren’t coming from a clear source? Or what if they look like something they aren’t, as is the case in false news stories or bot-powered “astroturf” groups? These forms of propaganda make it more difficult for us to find the facts we need to make decisions that are in our own and our country’s best interest.

Government-produced propaganda can also distort democracy by making it harder for us to accurately evaluate our leaders’ actions. Take, for example, this clip from a film the U.S. government produced to explain the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II. With some subtle shifts of language and a selective focus, it paints the program as a straightforward moral victory.

Not every propaganda campaign succeeds in achieving its goals. But when all else fails, propaganda makers can just rewrite the past to get the outcome they wanted. By replacing the facts with something more convenient and changing out some key vocabulary, a loss becomes a win. A violent campaign becomes an assertive demonstration of stability. The exposure of government corruption becomes a traitorous attempt to embarrass beloved leaders.

These revised retellings rob us of the chance to understand and learn from the past and make us more likely to repeat the same mistakes.

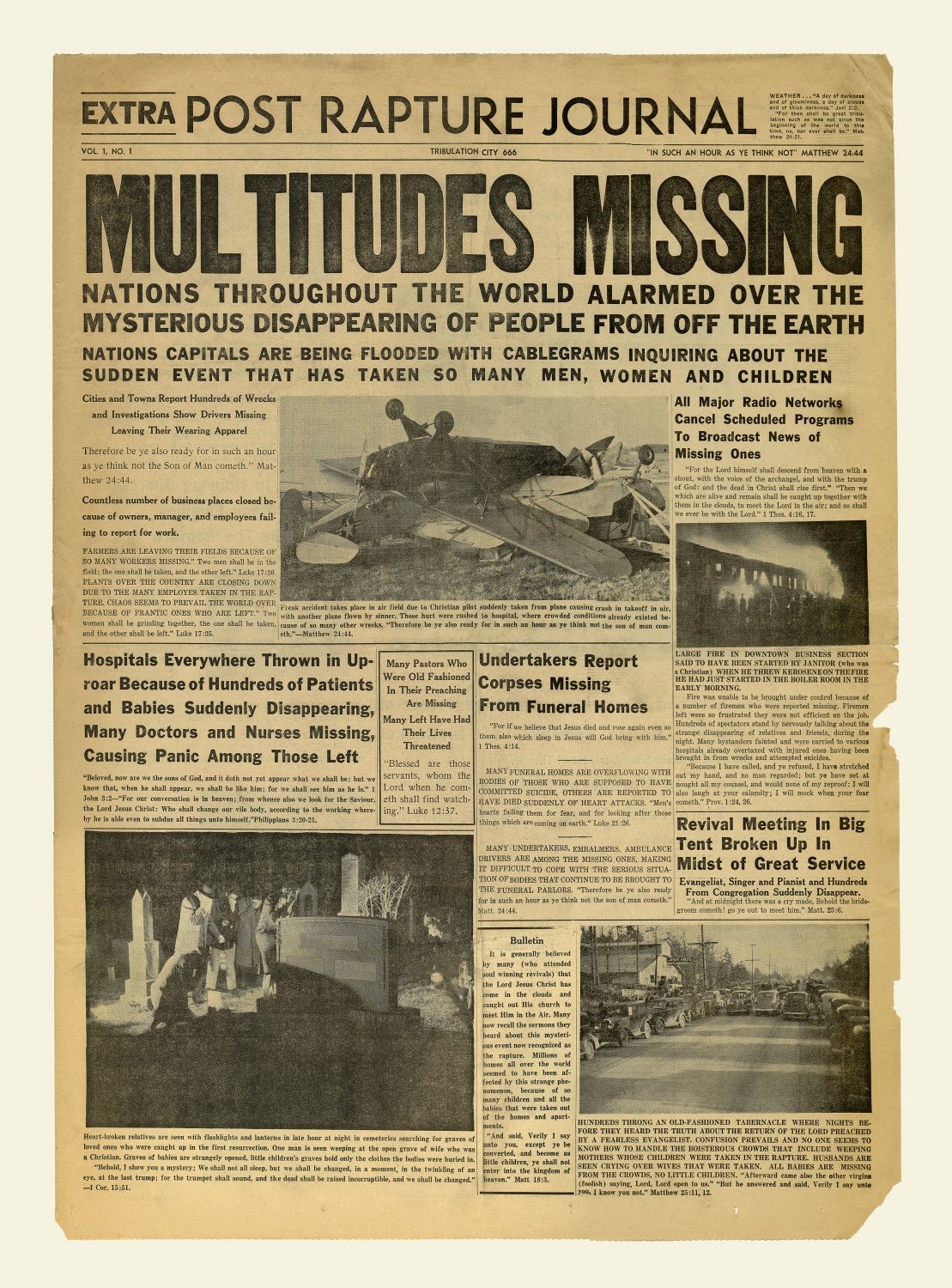

Fake news — not the insult hurled at mistakes in the media or reporting that makes you mad, but the existence of made-up news stories that try to look real — is itself a kind of propaganda.

Why does the problem of false news matter? Because it changes the way we all see the world.

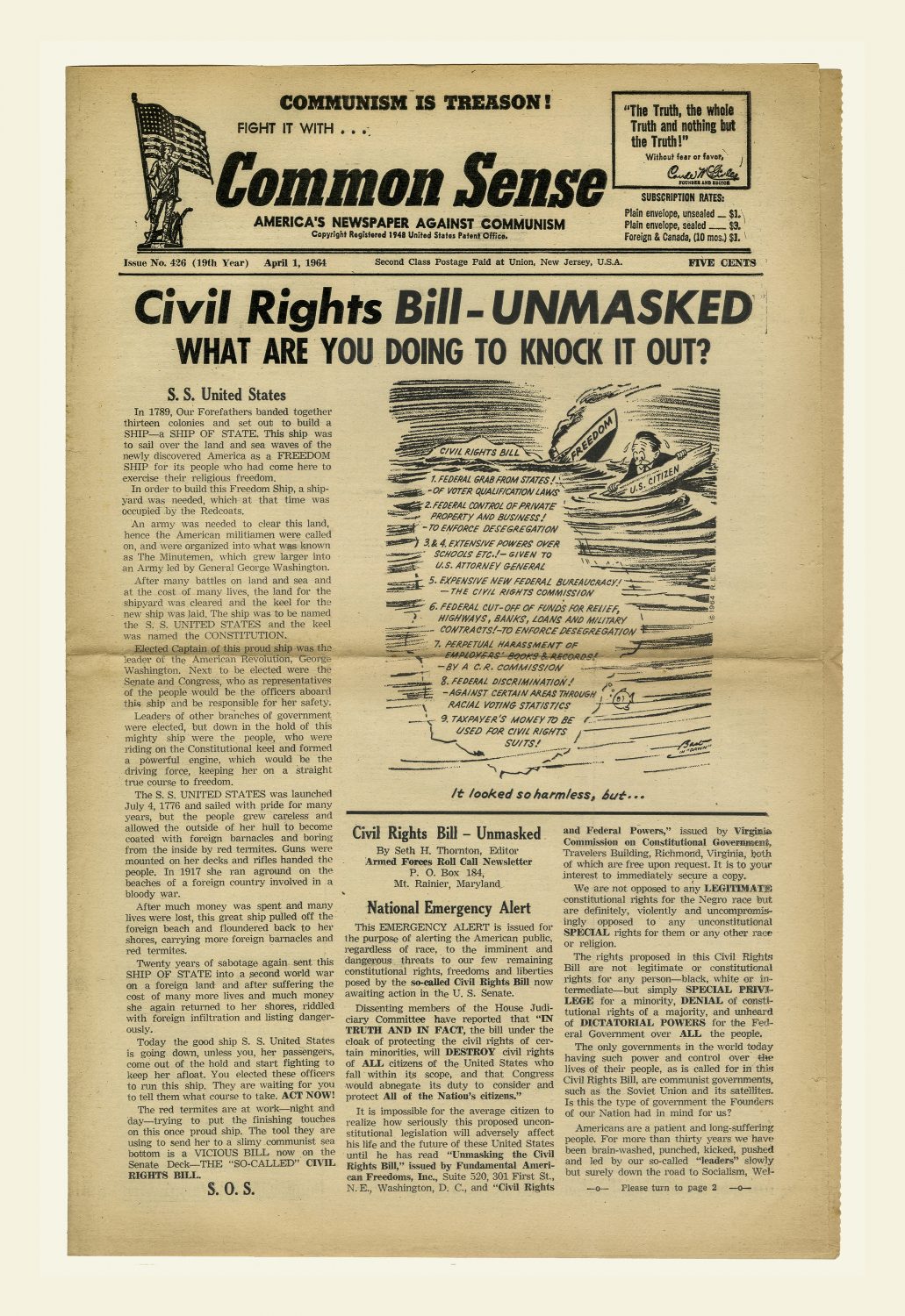

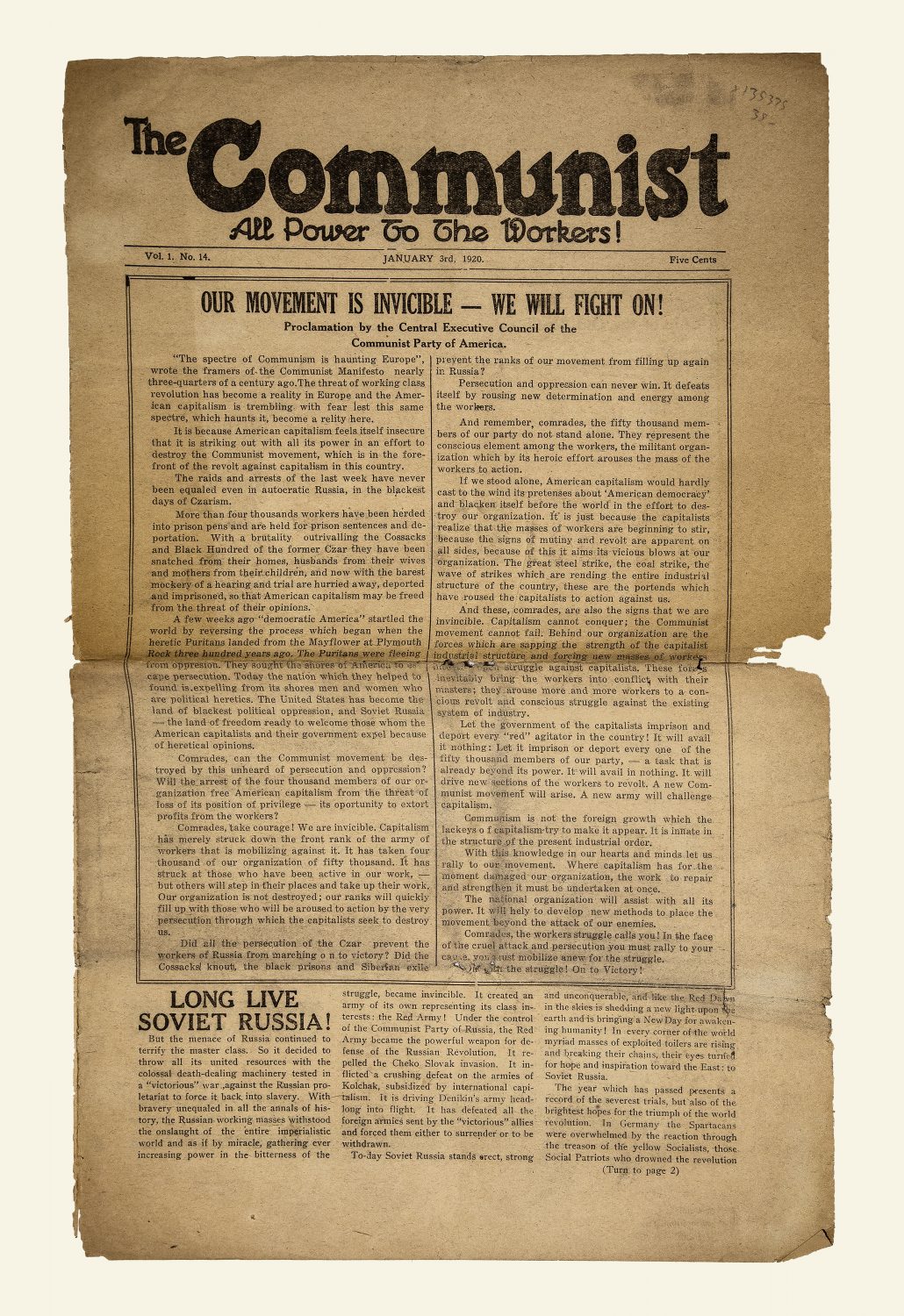

The problem of false news became widely acknowledged in 2016, with the revelation of fake stories about presidential candidates and electoral issues. But creating false news as a form of propaganda is not a new method of spreading disinformation. For example, in 1982, a TV Guide article warned Americans to beware of the fictitious stories that Russian operatives were planting in foreign media outlets.

Two hundred years earlier, Benjamin Franklin printed and circulated a fake account of British-ordered Native American attacks on colonists. Franklin hoped that British newspapers would pick up the story and that it would help generate British support for paying generous reparations to the “victims.”

Today, false news has made most people less sure of what to believe. A 2016 Pew Research Center survey found that nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults said “fabricated news stories cause a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current issues and events.” Even if these survey respondents often can’t agree on what constitutes a fully fabricated story and what’s just political spin, data suggests that many people feel increasingly unsure about what’s actually happening in the world.

To make matters worse, sheer exposure to these false reports can be all it takes for them to take root. Studies have indicated that seeing false information repeatedly can lead a person to eventually believe it. The brain begins to recognize the disinformation and interprets that familiarity as a sign that it’s true.

False news as a form of propaganda is unlikely to go away because it works.

Recently, the concept of deepfakes — videos in which a person convincingly appears to be doing or saying something they never actually did or said — has received increasing attention. If artificial intelligence can power the creation of videos where anyone can be made to say or do anything, is there any chance for keeping grasp of reality?

In the short run, there are many ways that propaganda can already twist the truth without needing to literally put words into someone’s mouth. These “cheapfakes” have been around for decades, using simple editing tricks to change the context or content of a real moment captured on video.

In the long run, deepfakes will become more common. Tips and tricks for spotting them are starting to emerge. But in the meantime, a check for that gut emotional reaction and for propaganda’s four manipulative techniques — simplification, exaggeration, exploitation and division — is your best bet for steering clear of all content where the looks may be deceiving.

Propaganda is information that's been molded to influence what you think and do — like clicking on this ad. It's time to #propagandaproof yourself.